Note: In case another trackback went out: never mind. I just updated the referenced article’s link which just keeps moving. (And again.)

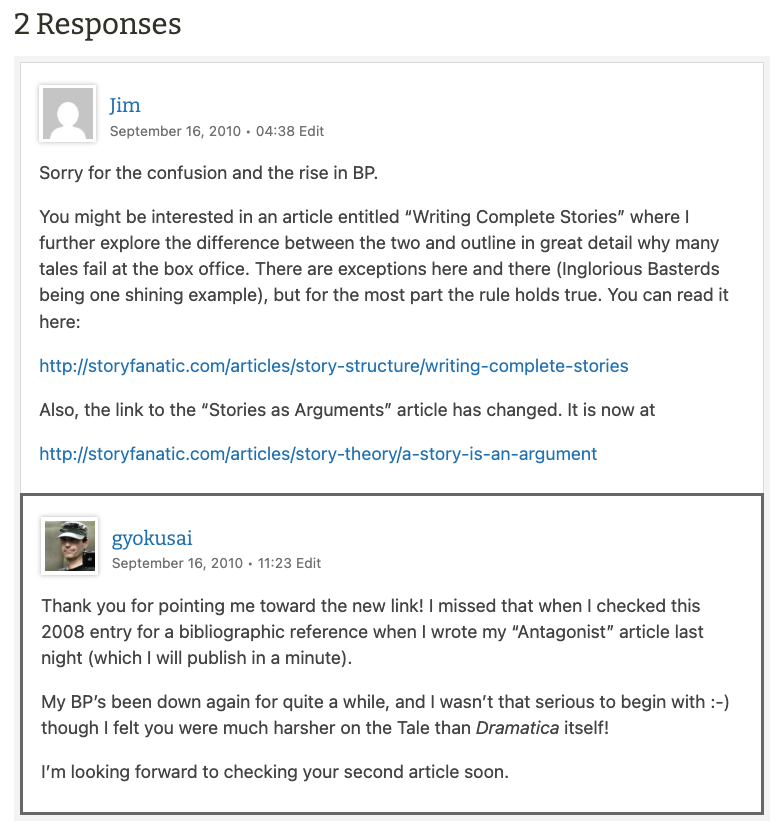

Plus, the two links James Hull provided in his comment below have moved to “Writing Complete Stories” and “A Story is an Argument”. Alas, our discussion in the original comment section over there has been lost in transition.

In “A Story is an Argument”, James Hull wrote two weeks or so ago:

There is a significant difference between stories and tales. A tale is merely a statement; a linear progression from one event to the next culminating in one singular outcome. It can be thrown out immediately and disregarded as a one-time occurrence primarily because it has relatively little to stand on. A story, however, offers much more to an audience member.

Although, in a footnote, he mentions that “[t]his concept of a difference between a story and a tale comes from the Dramatica theory of story,” I don’t think Hull makes it sufficiently clear that the Dramatica people deliberately construe this difference to advance their concepts. To quote from the affiliated book Dramatica: A New Theory of Story by Melanie Phillip and Chris Huntley1:

Dramatica differentiates between a “tale” and a “story.” If a story is an argument, a tale is a statement. Whereas a story explores an issue from all sides to determine what is better or worse overall, a tale explores an issue down a single path and shows how it turns out. (74–75)

Now that’s okay, sort of. They define and redefine a full cargo shipload of literary terms in order to develop the “Dramatica Theory of Story,” and it is made very clear—at times a bit more detailed, at times with shorthand phrases like “Dramatica differentiates…”—that this is how they define it for their purposes. But neither is it widely off the common mark in this case, as we’ll see in a minute, nor is it in any way dismissive or derogatory toward our little ugly duckling.

Which is why the latter raised my eyebrow and my blood pressure a bit, while Dramatica, some years ago, did not. So let’s check how Abrams’s Glossary of Literary Terms defines a tale.

In the tale, or “story of incident,” the focus of interest is on the course and outcome of the events, as in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Gold Bug (1843) and in other tales of detection, in many of the stories of O. Henry (1862–1910), and in the stock but sometimes well-contrived western and adventure stories in the popular magazines. “Stories of character” focus instead on the state of mind and motivation, or on the psychological and moral qualities, of the protagonists. [Examples from Chekhov and Hemingway ensue.] (194)

That sounds mostly harmless, and, refreshingly, even some good company’s been provided. We may add science fiction to the list, but maybe that’s covered by Abram’s “adventure stories,” together with a whole lineup of ancient and modern genre writing that’s also missing but would fit the bill.

Yes, genre writing and “tales,” in this sense, are certainly more event- and outcome-driven and less character-driven. However, there’s room a-plenty for the latter too. Oh, and to quote from Dramatica once more, “There is nothing wrong with a tale.”

Which sums it up nicely.

Concerning Comments

While I disabled comments ages ago, I preserved legacy comments. However, as each page with active comments throws a critical error for inexplicable reasons—even with all plugins deactivated—I attached all legacy comments as images with ALT texts instead.

If you have something valuable to add or some interesting point to discuss, I’ll be looking forward to meeting you at Mastodon!