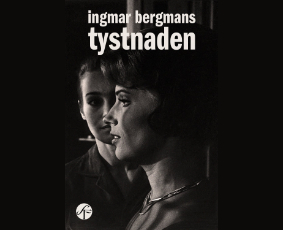

Tystnaden (The SIlence), Sweden 1963. Written and directed by Ingmar Bergman.

Eulenspiegel Theater, first row, center. Original version with subs.

(This post also appears at my Letterboxd account.)

First off, I neither buy into the notion that Ingmar Bergman’s 1963 Tystnaden aka The Silence is part of a trilogy; nor that the movie’s title means “the silence of god” in the sense it suggests it means; nor that the two main characters are “two sides of the same coin” as a “mind/body distinction” or some such. Because, respectively, Bergman himself backpedaled from the “trilogy” notion later; his “silence of god” remark must be read against the background of his preceding movies’ atheistic stand; and the Freudian coin stuff was, at the time around and after the movie’s release, very much l’interprétation du jour.

There are many antagonistic motifs in the movie that are pitched against each other, among them inward- vs. outward-directed loneliness, inward- vs. outward-directed lust, translation vs. incomprehensible languages; adulthood vs. childhood, health vs. sickness, Belle Époque grandeur vs. war-torn modernity*, but especially mutual grudges that the characters never addressed in their (unknown) histories, and thus allowed these grudges to grow into monsters.

Part of the titular “silence” might be the silence of narrative devices like backstory, plot, or music (there’s no non-diegetic music in the movie**, which, among other things, lets the movie’s sound design shine). And there’s even a “silence of location”—we never know where the characters return from, where they are, or where they’re going. The only thing that “speaks” is Sven Nykvist’s superb angle-, frames- and contrast-rich cinematography, which tells us a lot about the characters’ states of mind, but nothing beyond. Everything we think we know about the characters’ histories are, and remain, mere assumptions: that Johan is Anna’s son, that Anna and Ester are sisters, that the “father” they mention is the father of both Anna and Ester, or a father in that sense at all.

But that’s also a good thing because what we cannot know we can discard. We don’t have to spin some narrative around the characters for an interpretation (the U.S. publisher’s take on it was by far the wildest at the time of its release). We only have to look at what the characters and the camera do up on the screen and trace their dynamics, and nothing more.

If I had to settle on a theme that knits all the motifs mentioned above together, and also the title, the dialogues, and the setting, yeah, I would come back to what many others have proposed over time, namely old-fashioned “communication.” That’s not, granted, a particularly fresh take. But it might be interesting to reassess the movie’s verbal, non-verbal, and cinematographic languages from there along a structuralist/post-structuralist analysis from scratch.

________________

* Great juxtaposition here between the little boy with his toy gun roaming an immensely large deserted “old world” hotel (additionally enlarged by Nykvist’s use of wide lenses) and a large tank roaming the narrow deserted “new world” streets of the city at night that are too small for its size.

** Supposedly, there is some (originally uncredited) score by Ivan Renliden, but I can’t remember where or what that might have been. I remember, though, that a number of sound effects—industrial sounds, sirens, horns—almost come across as music; so maybe there actually is some non-diegetic score present, only heavily disguised as sound effects.

________________

All Movie Reviews

If you have something valuable to add or some interesting point to discuss, I’ll be looking forward to meeting you at Mastodon!