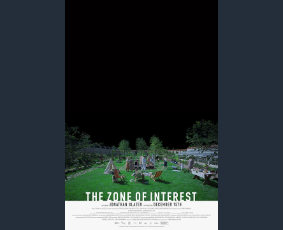

The Zone of Interest, UK/Poland/U.S. 2023. Directed and written by Jonathan Glazer, based on the novel The Zone of Interest by Martin Amis.

Cinema Theater, Row 2, Seat 11.

(This post also appears, in slightly different format, at my Instagram account betweendrafts.)

Movies about the Holocaust have always faced dilemmas.

Those that try to show the atrocities either fall short of their unimaginable nature and scope or become utterly unwatchable, each aggravated by ethical considerations as to the presentation of violence. Those movies that do not show the atrocities are often criticized for exactly that.

But their true dilemma lies not in violence but perpetrator representation. Displaying villains as evil, on the one hand, easily becomes cartoonish and even then doesn’t do justice to the unfathomable depravity of their crimes. Anything more nuanced, on the other hand, cannot but make these characters sympathetic, even if ever so slightly, owing to the inescapable intimacy of the camera–actor relationship as a cornerstone of cinematic representation.

Glazer defuses these dilemmas with two exceptional techniques. First, instead of showing the atrocities, the movie shows only their ubiquitous, pervasive, inescapable traces—from unequivocal sounds and visual cues to tradable goods and floating remains. Then, the movie breaks the camera-actor dynamic by filming with hidden remote-controlled cameras and without set directions. This, together with Żal’s eerily harsh-light wide-angle exterior shots, turns the Höss family’s fascist utopia into a flat dissection table that prevents any intimacy to build—which then renders the only exception, a brief low-angle close-up of Höss’s face inside the camp, violently nauseating.

Up to the belated midpoint (Watts’s cut is purposefully uneven), most of the dialogue is mundane and trivial and profoundly uninteresting—except for the occasional line that’s so offhandedly delivered it takes a second or two to realize that for the briefest moment, the curtain had been pulled back from the abyss.

Martin Amis’s novel provides the premise, but the horrors rather unfold in the tradition of Lanzmann’s Shoah and with a deep connection to what Arendt called the “banality of evil.” At the end, when Höss descends an ever darkening staircase, a peephole into the present appears, but only the audience is allowed a look.

________________

All Movie Reviews

If you have something valuable to add or some interesting point to discuss, I’ll be looking forward to meeting you at Mastodon!